Chapter 11: National and local disaster risk reduction strategies and plans

11.1 Sendai Framework monitoring data on Target E

As discussed in Part II above, the Sendai Framework monitoring system shows that Target E was reported on by 47 Member States in 2017 in relation to national strategies (Indicator E-1). This is a significant increase compared with 27 countries in 2016, but it is still less than 25% of Member States. Of these, 6 countries reported that they have national DRR strategies in comprehensive alignment with the Sendai Framework, while 16 reported substantial-to-comprehensive alignment, 15 moderate-to-substantial alignment, and 7 moderate alignment; 3 of the 47 reported limited or no alignment. However, using other sources of State self-reporting in addition to the formal SFM, the number is much higher, with 103 countries reporting having a national DRR strategy at some level of alignment, including 65 Member States that rated their alignment as above 50% (moderate to complete). This number is much more significant as it represents more than 50% of the United Nations Member States (Part II, Target E: Progress on disaster risk reduction strategies for 2020. Indicator E-1).

Target E also has an indicator on local strategies (Indicator E-2). It requires countries simply to report on the proportion of their local governments that have local DRR strategies. SFM indicates that 42 countries reported on local strategies. Of these, 18 reported that all their local governments have local strategies aligned with their national such strategies, and 7 reported no local strategies (or none aligned with their national strategies) (Part II, Target E: Progress on disaster risk reduction strategies for 2020. Indicator E-2).

Although the data on Target E thus remains partial, it indicates attention to the issue of aligning national and local DRR strategies and plans with the Sendai Framework, as well as suggesting there is still some way to go to meet this target by 2020. That said, it is also important to recognize that the global indicators are not designed to provide detail on the challenges countries face and what innovations and good practices they are developing to create the right enabling environment to reduce risk along the way to meeting the target. The essential purpose of asking for national strategies to be developed and implemented in alignment with the Sendai Framework is of course to do just that; to create the best national and local frameworks to reduce the wide range of risks addressed in the Sendai Framework. It is therefore important to look at the ways countries have tackled this issue.

11.2 Why are national and local disaster risk reduction strategies and plans important?

National and local DRR strategies and plans are essential for implementing and monitoring a country's risk reduction priorities by setting implementation milestones, establishing the key roles and responsibilities of government and non-government actors, and identifying technical and financial resources. While strategies are a central element of wider disaster risk governance system, it is important to point out that to implement effectively their policy, they need to be supported by a well-coordinated institutional architecture, legislative mandates, political buy-in of decision makers, and human and financial capacities at all levels of society.

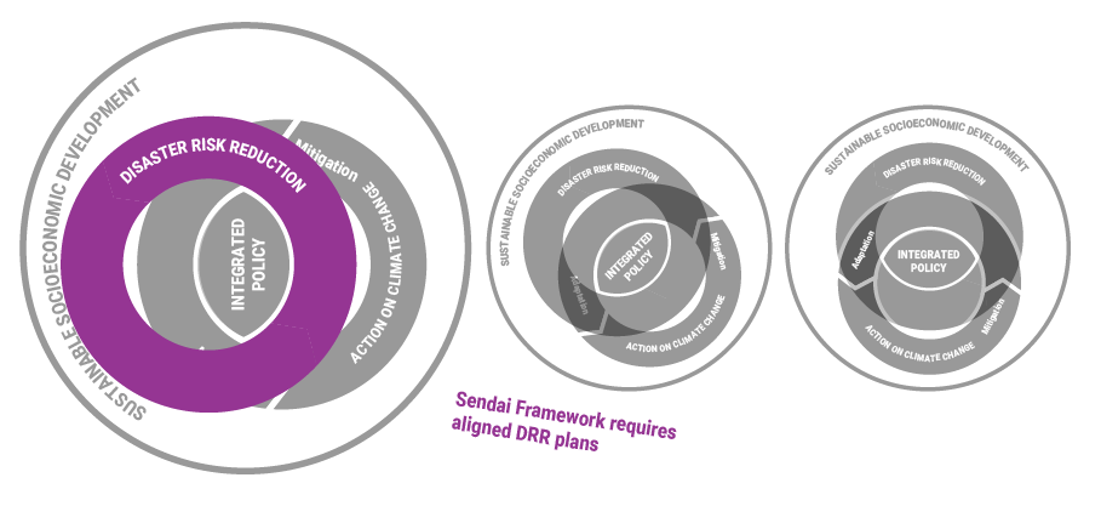

The Sendai Framework does not require countries to develop stand-alone DRR strategies and plans. However, it does ensure they have in place and implement national and local plans that do the job of supporting DRR in alignment with the Sendai Framework. Although there has been debate in the past about the merits of stand-alone or mainstreamed DRR strategies, in practice, this binary notion is not especially helpful in applying the Sendai Framework requirements. Under Priority 2: Strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk, paragraph 27(a) highlights the need to "mainstream and integrate DRR within and across all sectors and review and promote the coherence and further development, as appropriate, of national and local frameworks of laws, regulations and public policies." Paragraph 27(b) then advises Member States to "adopt and implement national and local DRR strategies and plans, across different timescales, with targets, indicators and time frames, aimed at preventing the creation of risk, the reduction of existing risk and the strengthening of economic, social, health and environmental resilience." Although the second paragraph mentioned was highlighted for the purposes of deciding indicators to achieve by 2020, the first paragraph is equally if not more important for achieving the ultimate goal and outcome of the Sendai Framework by 2030. This suggests that the precise form that a country chooses to pursue DRR at a strategic level is less important than the content and effectiveness of the strategies and plans in that country context.

Figure 11.1. The Sendai Framework requires aligned DRR plans by 2020 and recognizes the need for policy integration with development planning and climate action

In some cases, DRR may be integrated into broader national policy planning or DRM plans and strategies; indeed, this could meet the goal of integrating risk management and development planning. In contexts where awareness on DRR is emerging, stand-alone DRR strategies and plans can be used as an important advocacy tool to sensitize decision makers to take specific actions. But such strategies and plans should have among their objectives the integration of DRR into mid- and long-term planning processes, and to integrate them with managing climate risk where these areas overlap.

In many country contexts, stand-alone DRR strategies and plans are needed because their objectives are not automatically addressed through the national development or sectoral policy frameworks, or even within the systems established to manage disaster risk, many of which have traditionally focused attention and resources on response. This is often, though not necessarily, the case in countries with lower governance capacity where DRR strategies and plans compensate for risk management gaps in development or sectoral policies.

Clearly it is easier to point to and assess a single strategy, but this can also be in the form of a framework for integrated risk governance across sectors and ministries, addressing climate resilience and risk-informed socioeconomic development. In line with the Sendai Framework and 2030 Agenda, either mainstreamed or stand-alone risk reduction strategies should extend beyond the systems of civil protection or DRM and also include elements that are highly cross-sectoral in nature, such as urban risk management, land-use planning, river basin management, financial protection, public investment resilience regulations, preparedness and early warning, which cannot be addressed comprehensively through any individual sectoral strategy or plan.

DRR strategies, whether stand-alone, mainstreamed or a combination of both approaches, may also have a role in tempering market mechanisms, requiring public policy to address issues related to DRR as a "public good". Public goods are underprovided by the market, are non-excludable and create externalities. For example, individuals and communities may not construct sufficiently robust levees if they do not consider that their flood protection could help others, instead constructing levees that protect themselves only, which may even have a negative impact on those who live outside the embankments.

Having in place subnational and local DRR strategies or plans that complement the national policy framework has been increasingly recognized over the past two decades as an important requirement of a functioning risk governance system. The implementation of national DRR strategies hinges on the ability to translate and adapt the national priorities to local realities and needs. Local strategies or plans then allow for a much more nuanced territorial approach that fosters accountability through direct engagement with a range of stakeholders who need to be involved to avoid creating new risk, to reduce risk behaviours or to have a voice as the main groups suffering the impacts of disaster events. The penetration of DRR strategies or plans down to the local level is likely to depend on the level of practical decentralization, while the formal structure of government - centralized or federal - may or may not be a critical factor depending on the country context. As risk is not confined to any territorial or political division, it is also critical that DRR strategies or plans consider transboundary and regional solutions, such as basin- or ecosystems-based management, or arrangements that comprise multiple local government territories.

11.3 What does it mean to align strategies and plans with the Sendai Framework?

The Sendai Framework calls on national and local governments to adopt and implement these strategies and plans, across different timescales, and to include targets, indicators and time frames. They should aim to prevent the creation of risk, reduce existing risk and strengthen economic, social, health and environmental resilience. Importantly, Target E has also been reflected in two SDG indicators: (a) number of countries that adopt and implement national DRR strategies in line with the Sendai Framework and (b) proportion of local governments that adopt and implement local DRR strategies in line with national DRR strategies.

The Sendai Framework suggests several requirements to be covered by DRR strategies, and these have been distilled into 10 criteria for monitoring (Box 11.1).

Box 11.1. Drawing from the Sendai Framework, the following 10 key elements should be covered by DRR strategies to be considered in alignment with the Sendai Framework

- (i) Have different timescales, with targets, indicators and time frames

- (ii) Have aims at preventing the creation of risk

- (iii) Have aims at reducing existing risk

- (iv) Have aims at strengthening economic, social, health and environmental resilience

- (v) Address the recommendations of Priority 1, Understanding disaster risk: Based on risk knowledge and assessments to identify risks at the local and national levels of the technical, financial and administrative DRM capacity

- (vi) Address the recommendations of Priority 2, Strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk: Mainstream and integrate DRR within and across all sectors with defining roles and responsibilities

- (vii) Address the recommendations of Priority 3, Investing in DRR for resilience: Guide to allocation of the necessary resources at all levels of administration for the development and the implementation of DRR strategies in all relevant sectors

- (viii) Address the recommendations of Priority 4, Enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response and to "Build Back Better" in recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction: Strengthen disaster preparedness for response and integrate DRR response preparedness and development measures to make nations and communities resilient to disasters

- (ix) Promote policy coherence relevant to DRR such as sustainable development, poverty eradication and climate change, notably with SDGs and the Paris Agreement

- (x) Have mechanisms to follow-up, periodically assess and publicly report on progress.

(Source: UNISDR 2018)

It is assumed that DRR strategies and plans that meet all 10 requirements will create the best conditions to substantially reduce disaster risk and losses in lives, livelihoods, health, economic, physical, social, cultural and environmental assets. While all 10 criteria are important, a few stand out in terms of what is considered "new" about the Sendai Framework and its contribution to the global DRR policy agenda. These include a stronger focus on preventing the creation and accumulation of new risk, reducing existing risk, building the resilience of sectors, recovery, building back better and promoting policy coherence with SDGs and the Paris Agreement.

Policy coherence requires that national and local plans are aligned and designed for the context of the society and environment as defined by relevant hazards, high-priority risks and socioeconomic setting. Hence, the selection of risk reduction targets and the balance of different types of measures will be situation specific and will also depend on the risk perception and risk tolerance of the society represented by decision makers. However, making a mere reference to other relevant policies and strategies is not sufficient to meet this requirement. Done in earnest, establishing policy coherence depends on identifying common actions and instruments in support of shared policy objectives to reduce disaster risk or vulnerabilities, or to build resilience.

The 10 criteria recommended for assessing DRR strategies and plans against the Sendai Framework requirements are intended to ensure some consistency. But when the strategies or plans that have been endorsed since 2015 are compared, it is apparent that there is no "one size fits all". Depending on the national or local country context, DRR strategies can take a range of formats. Some countries pursue them as stand-alone DRR strategies, and others take the route of a system of strategies across sectors linked by an overarching document or framework. There is also a wide range of different strategic and hazard- or sector-specific plans in place, for example:

- In Norway, the National Disaster Risk Reduction Strategy is outlined in the Civil Protection and Emergency Planning White Paper

- In the Russian Federation, the National Disaster Risk Reduction Strategy forms part of the national security strategy

- In Luxembourg, which does not have a separate national strategy, DRR strategies are in place in specific sectors, as part of one or more combined strategies, such as with respect to flood risk management

- In Kenya, the National Disaster Risk Management Policy is complemented by the Kenya Vision 2030 Sector Plan for Drought Risk Management and Ending Drought Emergencies

- In Angola, a twofold approach is adopted with a Strategic National Plan for Prevention and Disaster Risk Management, covering three of the Sendai Framework's global priorities, and a National Preparedness, Contingency, Response and Recovery Plan, which covers the Sendai Framework's fourth global priority

- In Costa Rica, it was decided to align to the Sendai Framework through the adoption of a National Risk Management Policy 2016-2030 that provides a broad multisectoral mandate and is complemented by five-year National Risk Management Plans

Countries also choose a variety of names for their Sendai Framework aligned DRR strategies or plans such as: Master Plan for Disaster Risk Reduction (Mozambique); Joint Action Plan on Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction (Tonga); National DRM Plan or Strategy (Argentina, Colombia, Georgia, Madagascar and Thailand); Action Plan on Disaster Risk Reduction (Myanmar); National Disaster Risk Management Framework (Zimbabwe); or National Strategy for Disaster Prevention, Response and Mitigation (Viet Nam). These names suggest a much greater similarity when compared with the HFA aligned plans, which also used language related to civil protection, preparedness and emergency management, as in Burkina Faso, Canada, Dominican Republic, Kyrgyzstan or Mali, even though they addressed elements of DRR. Therefore, the title of the policy does not always indicate the extent to which it takes account of DRR or climate adaptation.

11.4 What are the lessons from the Hyogo Framework for Action and Sendai Framework

While the Sendai Framework monitoring requirements for Target E set high standards for assessing compliance, there are also other criteria that viable DRR strategies or plans need to meet to achieve results. These observations are derived from country-level experiences, mostly during the HFA implementation period, since such information on recently endorsed strategies under the Sendai Framework is not yet available.

Country experience suggests that there needs to be room for flexibility to adjust, evolve and adapt to changing contexts and priorities for strategies or plans to remain relevant and implementable. Hence, regular revisions and updates are strongly recommended. In particular, this relates to the activity level, where real-world changes need to be reflected, such as in the case of making the switch from printed hazard maps to online information systems, as in Tajikistan. In addition, implementation needs to be supported by financial and technical resources, and operational guidelines and tools that are commensurate with the available capacities and skills of those involved.

Implementation also benefits from having subnational and local strategies or plans in place that are linked with national DRR and development policy priorities. Good examples of this practice are known in India, Indonesia and Mozambique. Implementation plans at different scales of governance can be either stand-alone, as in Bangladesh or Sri Lanka, or they can be integrated into local development plans as in Kenya. In some instances, countries pursue a hybrid solution where subnational DRR plans exist in parallel with local development plans that integrate risk considerations, as the below example from Mozambique shows.

With regard to the process of drafting or developing DRR strategies or plans, there are now increasing calls for them to be grounded in a comprehensive "theory of change" that allows for a better understanding about how beneficial, long-term change happens. This means that strategies and plans are produced through a process of reflection and dialogue among stakeholders, through which ideas about change are discussed alongside underlying assumptions of how and why change might happen as an outcome of different initiatives.

The involvement of multiple stakeholders is already a key principle of the Sendai Framework, and essential when it comes to seeking agreement on and setting the DRR priorities at different levels of government. Ensuring active participation of women, persons with disabilities, youth and other groups who may not automatically have a seat at the table is a prerequisite for ensuring that their needs are addressed, and their specific knowledge and skills accessed. Calls for the recognition of the right to participate in DRM decision-making, in line with the right to self-determination and access to information, are becoming more frequent. This will also require an understanding of the incentives, interests, institutions and power relations facing key stakeholders engaged in risk-reducing and risk-creating behaviours. Hence, understanding the political economy of DRR will be an essential step for insuring the involvement of all interest groups.

11.5 What good practices are emerging at national and local levels?

11.5.1 Triggers to review or develop strategies

The most obvious impulse for countries to develop or revise their existing DRR strategies or plans is Target E. For example, Costa Rica, Montenegro and Sudan assessed their current strategies and concluded that they were out-dated and did not meet the requirements of the Sendai Framework and other international conventions. Kyrgyzstan and Madagascar identified the need for a new strategy that was able to better address changes in the internal and external environments, meet the principles of sustainable development and be part of the national development strategy. A working group was established within the National Platform, which led the drafting process of the strategy and implementation plan in 2016-2017, which was the approved in January 2018.

In Kyrgyzstan, parliamentarians and heads of the Ministry of Emergency Situations and other State bodies participated in the Sendai conference in 2015. This was the impetus for the Government of Kyrgyzstan to instruct the Ministry of Emergency Situations and other State institutions to consider ways to implement the Sendai Framework. They undertook stakeholder consultations, and then the Ministry of Emergency Situations and the National Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction submitted a proposal for consideration by the government on the development of a new strategy. During 2016-2017, the National Platform led the drafting of the strategy and an implementation plan; the National Disaster Risk Reduction Strategy was approved in in January 2018.

Another important impulse has been the occurrence of major disaster events and the realization that sustainable development is difficult to achieve in the face of the pervasive damage from disasters. For example, this was the case after the 2016 drought in Mozambique, and the 2017 floods in Chiapas, Mexico. In Argentina, a host of developments following the 2015 floods in Buenos Aires Province paved the way for a DRM policy overhaul in line with the Sendai Framework, with support from the Federal Congress for Disaster Risk Reduction and the National Congress for Disaster Risk Management, the passage of a new DRM law (No. 27287) in 2017 and a national plan in 2018.

Another typical trigger for developing or reviewing DRR strategies or plans can be the enactment of new legislation. This has been the case in the Philippines during the HFA implementation period, where the 2010 Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act tasked government with developing a comprehensive DRM plan and framework. Also, the new DRM law (2015) in Argentina mandated the elaboration of a National Disaster Risk Reduction Plan. Strategies or plans can have a role in supporting the law reform process by providing details for the implementation of new and more ambitious laws. They can also extend the reach of out-dated laws by advancing the focus on DRR or requiring DRR to be integrated into development, as was the case in Nepal until the new Disaster Risk Management Act was endorsed in 2017.

No matter what is urging countries to align their strategies with the Sendai Framework, it is important that a self-sustaining process is initiated that can keep stakeholders motivated to keep the strategy alive over an extended period of time. This is particularly important at times of infrequent disasters when the memory of devastating impacts is fading. Periods that are free from major disasters provide the best opportunities to focus efforts on reducing the accumulation of new risks while also tackling existing risks.

11.5.2 Foundations in assessment

Although it appears self-evident that risk analysis precedes priority setting and planning, it appears this is not yet a common practice. Resource constraints often lead to short cuts when it comes to the analysis stage; many strategies or plans therefore identify risk and capacity assessments as a key output to be produced. This may be a fair and pragmatic solution, if indeed the assessments are conducted, and their results used to review or refine the original DRR strategy. While the importance of both local and scientific knowledge is usually highlighted in the assessment process, in practice, it appears that scientific knowledge tends to be preferred in formal strategies.

In Europe and Central Asia, risk assessments and disaster loss databases have been identified as essential building blocks for the development and implementation of national and local strategies. Low-risk awareness is one of the main challenges, not only when it comes to setting the right DRR priorities but also in implementing DRR strategies. Having access to risk information is therefore an important first step. Haiti, Mexico, Rwanda and Uganda have made great strides in understanding their risk profiles by developing national risk atlases, which provide a comprehensive assessment of existing risks at the national and local level in areas that are highly risk prone. The risk assessments and profiles are updated and expanded and are reportedly informing the ongoing process to align the respective DRR strategies and plans with the Sendai Framework.

In Colombia, the preparation of the National Disaster Risk Reduction Plan 2015-2030 was preceded by the development of a risk management index and a diagnostic of public expenditures for DRM in 2014. Tajikistan is another interesting example of a government making a deliberate effort to take into consideration emerging threats in developing a new strategy. The country's increasing scale of industrialization and mining is expected to create new risks related to hazardous wastes and the growing volume of goods transported by road. These require risk management measurements that the Government of Tajikistan is not sufficiently familiar with. Also, so-called legacy threats from radioactive materials will require greater attention as they are technically complex and often beyond the means of local capacities.

Namibia's National Disaster Risk Management Policy from 2009 was revised in 2017, in line with the Sendai Framework. The subsequent Disaster Risk Management Framework and Action Plan (2017-2021) draws upon the findings and recommendations of a national capacity assessment facilitated by the United Nations system through the Capacity for Disaster Reduction Initiative and the United Nations Disaster Assessment and Coordination. The recommendations of the assessment were endorsed by the National DRM Committee in February 2017. Following the endorsement, a stakeholder consultation process has been rolled out at national and subnational levels to prioritize actions, assign responsibilities, and agree on budgetary and timeline requirements across institutions, sectors and governance levels. Other examples of DRR strategies and plans that were based on comprehensive cross-sectoral capacity assessment, include those of Côte d'Ivoire, Georgia, Ghana, Jordan, Sao Tome and Principe, and Serbia. In Sudan, a SWOT (strength-weaknesses-opportunities-threats) analysis laid the foundation for identifying gaps in the DRR policy framework and emphasized the need for the new strategy to better consider the local risk context.

11.5.3 Engagement with stakeholders

Most plans have been developed through some form of collaborative multisector arrangement. Inter-agency working groups, often linked to a country's National Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction, or inter-agency coordination mechanism, are usually guiding the process with representation from ministries, departments and other interested parties, such as NGOs, local governments, academia and the United Nations, like in Guatemala, Kyrgyzstan, Montenegro and Peru. In Sudan, a dual mechanism of a task force and technical committee provided oversight and strategic guidance.

However, broad engagement is not always a guarantee for success. For example, in Tabasco, Mexico, the Civil Protection Master Plan of 2011 was developed in a participatory process by representatives of all state government ministries under the leadership of the Ministry of Planning. Despite the political will this process had generated the plan was only partially implemented. This indicates that a range of other factors can influence the level of implementation.

There are also countries in which the national DRM authority spearheaded the drafting process, as was the case in Colombia, Costa Rica and Mozambique, by seeking inputs on the draft text through consultations in a subsequent step. The Ministry of Local Affairs and Environment was the driving force for the strategy development in Tunisia

11.5.4 Policy coherence

Overcoming the siloed approaches and duplicative efforts in implementing DRR, climate change and sustainable development stands at the centre of the 2030 Agenda and is also ingrained in the Sendai Framework. In aspiring to tap into synergies among these interconnected policy and practice areas, and to overcome the related competition over resources and power, only a few countries have made good advances on this Sendai Framework requirement.

In Montenegro, the main hindrance noted during development and implementation of the strategy was that decision makers and stakeholders did not come with prior knowledge of the fields of DRR, SDGs and climate change, including how these areas interact. A spot check of several Sendai Framework aligned strategies and plans has revealed that this requirement is not, or only superficially, met. As noted in section 10.4, and discussed further in section 13.5.1, this is not the case in the Pacific region. There, FRDP provides high-level strategic guidance to different stakeholder groups on how to enhance resilience to climate change and disasters, in ways that contribute to and are embedded in sustainable development. Under FRDP, Pacific Island governments are called to provide policy direction, incentivize funding to support implementation of coherence initiatives, ensure cross-sectoral collaboration and take measures to gauge progress. Tonga's Joint National Action Plan (JNAP) on CCA and DRM (2018-2028) is one such example of a coherent approach to resilience building, which is anchored in SDGs and other relevant global and regional policy instruments. This is also highlighted as a national good practice case study in section 13.5.2. A key element of Tonga's second plan, JNAP II, is a strong focus on the development of sectoral, cluster, community and outer island resilience plans that fully integrate climate resilience and practical on-the-ground adaptation, reduction of GHG emissions and DRR. Other countries' DRR strategies and plans, such as those of Vanuatu and Madagascar, also take account of risks related to climate change. Other positive examples of policy integration, between DRR and CCA, are discussed in Chapter 13.

11.6 Conclusions

Governments have many instruments of public policy at their disposal that can be used to influence the risk-generating or risk-reducing behaviour of the general public and the private sector. DRR strategies and plans are only one such instrument, along with laws and regulations, public administration, economic instruments and social services. Despite the development of such strategies over a span of two decades, it appears that national disaster risk governance systems are often still underdeveloped; this is potentially a serious limit for implementation of the Sendai Framework.

Looking at the contents of strategies and plans, considerable gaps still exist, especially regarding the newer elements, such as preventing risk creation, including targets and indicators, and guaranteeing monitoring and follow-up mechanisms. Surprisingly, some of the more established elements are also not consistently addressed in the strategies reviewed, such as clear roles and responsibilities, and methods to devise and deliver local strategies.

It is nevertheless encouraging to see that there is a growing number of countries which see the value of the process, and are making a greater effort to devise more inclusive and consultative approaches to discuss and agree on their DRR priorities.

At this stage, there is little to report on the level of implementation or impact of Sendai Framework aligned strategies, as many of them have been endorsed only in the last 12-18 months. But there are early indications that the challenges encountered during the HFA decade still apply, despite many good practices and examples. With the 2020 target date fast approaching, and given the role of DRR strategies or plans as key enablers for reducing disaster losses, their development and implementation in line with the Sendai Framework needs to be made an urgent priority at country level.